Heartbleed heartache: This was not a drill, people, and you failed

After a week of Heartbleed, the SANS Institute's Internet Storm Centre (ISC) has dropped back to INFOCON Green. No longer is it a yellow alert, requiring "immediate specific action to contain the impact". Things are back to normal. So let the blaming and finger-pointing begin!

I'll start, shall I?

As a whole, the internet industry was absolutely shocking at providing end users with coherent or even accurate information about what was going on, let alone information they could understand and act upon — and, at least here in Australia, the government did nothing to help. Not good enough.

Think I'm being harsh?

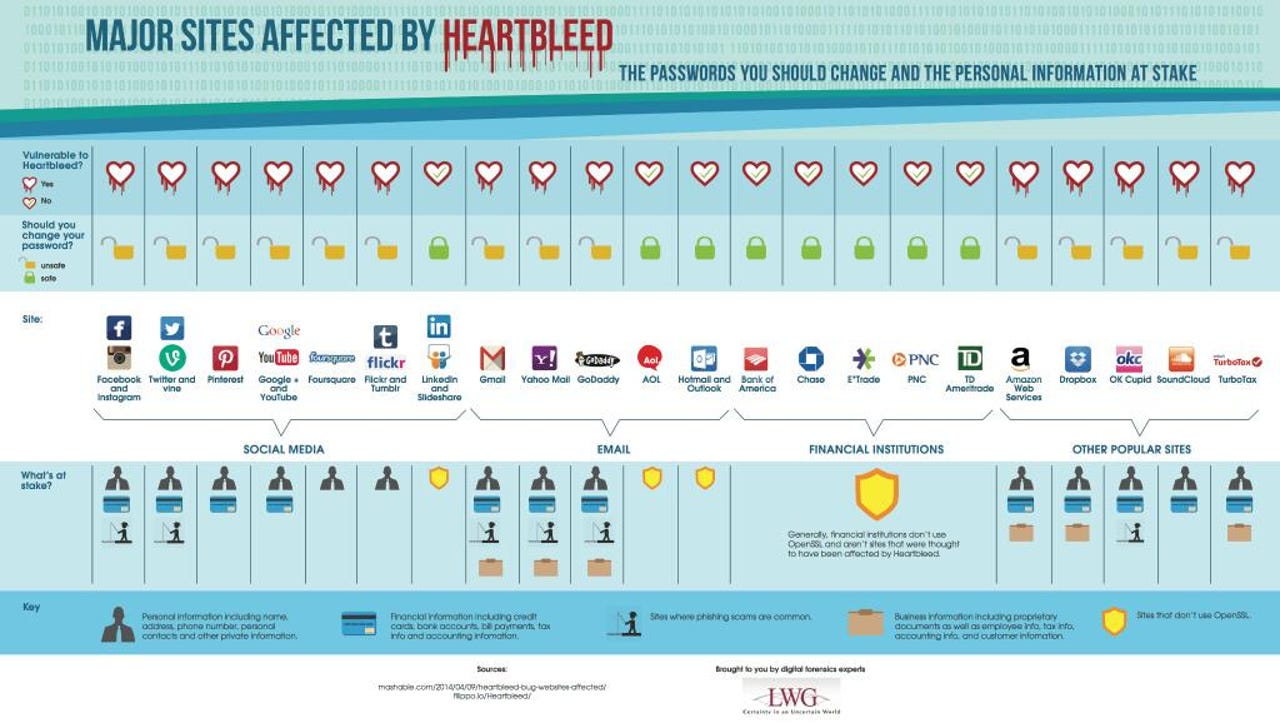

Remember that Heartbleed was not a drill. Initially, we thought that up to two-thirds of the world's encrypted web traffic might have been at risk. It turned out to be somewhat less than that. Nevertheless, the affected services included Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Vine, Pinterest, Google, YouTube, Gmail, Foursquare, Flickr, Tumblr, Yahoo! Mail, GoDaddy, Amazon Web Services, Dropbox, OKCupid, SoundCloud... and they're just the ones listed on one infographic from LWG Consulting.

Add in Akamai and Cloudflare, and all the others you've heard about, and you're talking about a hefty slab of the world's websites, large and small.

Here in Australia, Fairfax is now reporting that financial websites run by GE Money were vulnerable to Heartbleed, including the Myer Visa Card and Myer Card portals, as well as Coles Mastercard.

Now consider the start of a conversation I had on Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) radio stations across Victoria and Western Australia on Monday night — a full week since news of Heartbleed started to seep out from under the infosec community's moth-eaten cone of silence.

More Heartbleed

"Is is safe yet to go back onto the internet? We've probably heard, to varying degrees, about this Heartbleed vulnerability — not a virus — it's an internet vulnerability. But we've been told to steer clear of the internet — well, I've been told to steer clear of the internet for a while — and change all my passwords," said presenter Prue Bentley in her introduction.

As a radio presenter, Bentley is someone who actively seeks out information. Moreover, my understanding is that she's a bit of a geek. The previous items on her program had been a chat with a former chief of the Royal Australian Navy's submarine fleet about the state of the art of underwater drones, and a lively chat about movies in which she displayed considerable knowledge of Gattaca, a science fiction classic.

Yet even though Heartbleed had been in the news for a week, Bentley still didn't know what she was meant to do. Like almost every user, she must have been affected in multiple ways — but, she told me, she'd received only one notice, from one small provider.

That's not good enough.

So why did it happen that way?

I contend that while infrastructure providers and some major players were sorting out the mess — some, like Akamai, with commendable transparency, even when things were going badly, others not so much — the vast majority of consumer-oriented operations and small players were more interested in saving face than in saving users' private data.

The infosec specialists who present the Liquidmatrix Security Digest podcast discussed Heartbleed — more ranty that usual, and well worth listening to — reminded us, amongst other things, that the customers of smaller IT shops and software as a service (SaaS) providers are businesses that are even smaller still, and those SME and home users typically have no idea what any of this security stuff means.

Telling those customers to change their passwords because you've patched some mysterious security hole breaks the bond of trust. "Why are you having to fix problems? The other guys don't keep telling me about problems, so you must be incompetent," they think. That's not exactly an incentive to be open, honest and transparent. It's tempting to keep shtum, and hope nobody notices.

Now in similar situations outside the IT world, it's the government's job to make sure people at risk get reliable information. As I wrote at Crikey, if the front door locks on two-thirds of Australian businesses could be opened with a pocket laser, without being detected, or if two-thirds of all cars could be stolen at some time in the future unless their owners took specific action this week, we'd be seeing a recall program, advertising in mainstream media, perhaps a government-funded public awareness campaign, certainly front-page headlines and calls for assistance and for heads on spikes.

But for all the talk in recent years about the imminent cybergeddon, or even a devastating refrigergeddon, the reality seems to be that we've got nothing approaching even a bare-bones civil cyber defence system.

When I called CERT Australia early in the Heartbleed scare, they referred me to their masters at the Attorney-General's Department. Fairfax journalist Ben Grubb had already done that, and the response he received was... minimalistic.

"As the national computer emergency response team, CERT Australia provides major businesses with information about unique cyber threats and support in responding to cyber security incidents upon request, including issues such as the Heartbleed vulnerability in OpenSSL," an Attorney-General's Department spokesman said in a statement.

"There is a range of open source information available about the Heartbleed vulnerability and the actions to take to address it. Useful resources are available at http://heartbleed.com/."

CERT Australia is only a small coordinating unit, and they were undoubtedly busy. Nevertheless, is it really good enough for the nation's official cyber coordinator to tell people, in effect, "You're on your own, go look on the internet"?

I don't blame the hard-working staff of CERT Australia here. I point my finger directly at the Attorney-General's office. No words can issue from CERT Australia without their say-so.

But Australia's favourite Attorney-General, Senator George Brandis QC, for all his talk of law and order, seems to have had precisely nothing to say about a real-world security risk that affected nearly every Australian online. Sigh.

We'd have been better off with a cyber-update of Bert the Turtle.